REA Offices at Flatiron

Location: Downtown Oklahoma City, Flatiron District

Client: Rand Elliott Architects

Project Type: Restoration/Renovation and Corporate/Offices

Scope: 5,080 SF (Floors 1 & 2) + 1,996 SF (Basement Library)

Completion: May 1995 + Aug 2011

Photographer: www.hedrichblessing.com (Robert Shimer)

Description: Architecture transforms light into spirit.

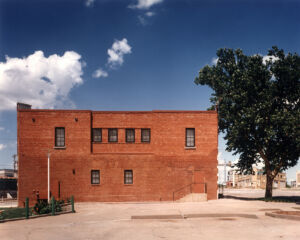

A Landmark Building, Reborn

Downtown Oklahoma City’s 1911 Heierding Building is on the National Register of Historic Places. It served generations as Heierding Meat Market, a beloved mom-and-pop neighborhood enterprise with family members living in the upstairs apartment. They were part of a large population of German immigrants; surprisingly, the city was once served by as many as 10 German newspapers.

A Legacy: Heierding, Belt, Elliott

Patriarch August Heierding fed the poor during the Depression and his fine brick building was one of the first in OKC to install air conditioning. But after the market closed in 1968, it fell into disrepair, and a 1981 fire destroyed all but the shell. Wisely, the same preservationist and civic citizen known for saving the Paseo District, John Belt, had purchased the property so it wouldn’t be razed. Yet it continued to languish, empty.

In 1992, Rand and Jeanette Elliott bought and brought new life to the building. They were downtown believers before the renaissance that would soon arrive with MAPS 1 and weren’t dissuaded by the charred interior. The building had good bones – its red brick and its elegant ornamentation were intact, as was the triangular footprint. It was ready to be revived.

Preserving OKC’s “Flatirons”

The building’s distinctive “flatiron” (triangular) shape was set forth in 1903 when the Oklahoma City streetcar system laid tracks on a diagonal, angling to and from the turnaround at Stiles Circle (Oklahoma’s first city park, highlighted today by the Beacon of Hope in OKC’s Innovation District and named for lawman and pioneer settler, Captain Stiles). The short, diagonal street was named Harrison Avenue, a popular choice of the era in many American towns.

The first building to take on the term, “flatiron,” was the triangular 1902 skyscraper in midtown New York City by famed architect Daniel Burnham. Its wedge-shaped lot resembled a what was then used as “smoothing iron” for clothing (not hair!), heated on coals before electricity arrived. Soon, there were flatiron buildings across the country, popular for their unique shape and popularity among photographers. The view from outside the pointed “prow” is the classic flatiron view.

The Elliotts’ Flatiron stands nose-to-nose with the 1924 former Como Hotel (which Rand Elliott Architects restored in 2015, adding a third floor and creating modern offices for PLICO).

The streetcar laid the groundwork for nine flatiron-shaped buildings built, but

most were lost in mid-20th century when construction of the adjacent interstate I-235 took out much of the Deep Deuce neighborhood. The last historic flatiron to fall was a large laundry operation just across Harrison Avenue.

This left Rand Elliott Architects’ home and its neighbor to the east, PLICO, as the sole surviving true “flatirons” created by the Harrison Avenue’s diagonal path. Like wedge-shaped islands with their architectural integrity intact, both structures stand at the nexus of several intersecting streets.

Recasting the Role of “the Heierding”

For the REA team the object was to bring the surviving building exterior to its original 1914 condition and redefine it as an inspiring, functional, office space for practicing architecture.

ADA requirements were met without compromising the integrity of the historic structure.

The restored interior is modern, highlighting historic architectural elements and demonstrating the opportunity to combine architectural preservation and modern thinking. In fact,moving REA offices back downtown in 1995 set an example in the area, demonstrating the importance and impact of preservation.

Reclaiming History, Telling Tales

REA restored the sidewalks and adjacent parking lot, nurtured a couple of majestic legacy trees and established other landscaping. A “patch of green” was planted on the adjacent property, reducing the heat island effect on a small scale.

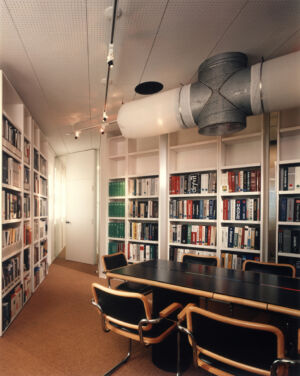

A gallery/conference space on the first level accommodates meetings, small social gatherings, the display of project photographs and changing artwork. Historic charm abounds in stairways of tall walls of exposed brick, stamped with their foundry, Kenyon Brick & Tile Co.

Architectural Concept: “Light Shrines”

It was the goal to use light as a design element and “paint with light.” Light is the art and the spirit of the space.

Six special “moments” throughout illustrate how light (daylight and electric) can behave as it interacts with the architecture. It’s an example of Rand Elliott’s mantra, “Place, Purpose, Poetics.”

Light Shrine 1

A bare bulb hanging from the ceiling at the “nose” of the building that emits the “energy” of the building. It remains on, 24/7 and represents the firm’s promise of original ideas.

Light Shrine 2

The triangular reception space is formed by theater scrim “holding” the shadows from exterior windows and the light “captured” inside.

Light Shrine 3

A lighted “slit” panel in the men’s toilet, visible through the clerestory glass.

Light Shrine 4

Lighted stair risers allow their user to “walk on light.”

Light Shrine 5

A back-lighted roof drainpipe illuminates the acute-angle corner of the interior brick.

Light Shrine 6

Solar mesh “light walls” divide the studio workstations.

One objective was using common materials in unusual and thought-provoking ways, showing visitors new possibilities in creative thought. Examples:

• 12-foot-long pull chain switches used instead of wall switches.

• Theatrical scrim used as a space divider instead of glass. It was necessary to use “zoned sound” to create acoustical privacy between spaces.

• Perforated hardboard ceilings with batt insulation above acts as an acoustical surface. The diagonal alignment reveals joints for the structural framing above.

• Clear fiberglass pipe normally used for solar water storage tubes are incorporated as ductwork to communicate that air is invisible and “light.”

• High-tech nylon fabric is used as air supply ducts in the studio. It “breathes” as supply air is discharged into the space.

• Fiberglass mesh solar shades are used on the interior to form “light walls” at workstations to soften the light and create a better ambiance for computer use.

Awards:

AIA Central States Region, Citation Award; AIA Central Oklahoma Chapter, Merit Award

24th and 25th Annual International Illumination Design Awards, Awards of Merit,

AIA Central States Region Citation Award of Excellence and Honor Award,

Oklahoma State Historic Preservation Conference Citation of Merit,

Downtown OKC’s Phoenix Award, Oklahoma Historical Preservation and Landmark Commission Honor Award, Oklahoma City Beautiful Environmental Improvement Award.

Media: Cover story of Downtown magazine, an extensive Journal Record article.

Full Gallery